Early 1960s accidental deaths of two infielders likely cost Cubs and White Sox several pennants in the late 1960s and early 1970s

The Chicago Cubs and Chicago White Sox perennial pennant contenders and pennant winners?

As unlikely as this scenario seems, the teams were headed that way in the 1960s—until fate stepped in and took the lives of two young men who were great ballplayers—and great people.

Cub fans of a certain age remember the Williams-Santo-Banks Cubs of the 1960s and early 1970s, and how close they came to winning the pennant, particularly in the years 1967-1973. One or two more good players could have gotten the Cubs not only one pennant, but several.

Few people remember that they had a player who was not only good but great, but was tragically lost.

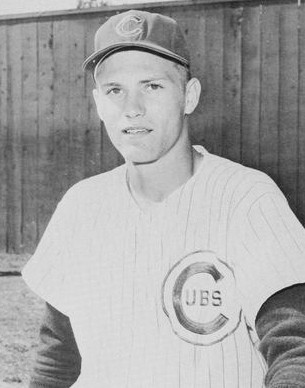

That player was second baseman Ken Hubbs.

Hubbs was only the second Rookie of the Year in Cubs’ history. After Billy Williams won the award in 1961, Hubbs followed up as Rookie of the Year in 1962.

People may look back at Hubbs’ two full years in the majors, 1962 and 1963, and be unimpressed with his batting. He hit a respectable .260 in his Rookie of the Year season in 1962, but his batting suffered from the sophomore jinx in 1963 when he hit a mediocre .235.

But Hubbs’ value to the Cubs generally wasn’t at the plate. Hubbs in only two years proved to be one of the most sensational fielders in major league history.

He was the first rookie in baseball history to win a Gold Glove Award in his rookie season. He set several fielding records that year, and easily won Rookie of the Year.

As a 13-year-old, Hubbs played shortstop in the 1954 Little League World Series. In that series, there was a play in which he ran all the way from shortstop to right field to catch a fly ball. And he did that despite playing the whole Little League tournament that year with a broken toe.

So with Hubbs’ incredible range, having him in the infield was like having a tenth player on the field. In Chicago softball leagues, there is a tenth player called the short center, who serves as an extra infielder and outfielder. When Hubbs was playing second base for the Cubs, it was like they had a short center too.

In an era when most middle infielders were the shorter guys on the team, Hubbs, at six-feet, two-inches, could both reach groundballs that would elude most infielders, and pop flies that would go over most infielders’ heads.

Like Michael Jordan for the Bulls in the 1990s, Hubbs was a gamer: he wanted to play all the time whether he was injured or not. Not only did he play in the Little League World Series with a broken toe, but in high school, Hubbs broke a foot before a football game. So with the foot in a cast, he got a size 14 shoe from somewhere, put the shoe over the cast, and played anyway. With Hubbs around, just like with Michael Jordan around, nobody else on his teams ever malingered or sat on the bench with a minor injury.

Hubbs was a multi-sport star. Notre Dame wanted Hubbs to play quarterback. John Wooden wanted him to play basketball at UCLA. Instead, Hubbs chose the Chicago Cubs. After signing with the Cubs he played in what was then called the Class D minor leagues in 1959, and was nominated for Class D player of the year.

With Ernie Banks at shortstop for the Cubs, the team wanted Hubbs to switch from his natural position of shortstop to second base. In that era, by the way, the Cubs had an all-star second baseman in Don Zimmer, but they knew Hubbs was going to be better and wanted to make sure there was a place for him.

In September 1961, the Cubs brought up two rookies to the major leagues, Ken Hubbs and Lou Brock, and they made their debut the same day on Sept. 10. Their sharp play caused Cub fans to hope that they would be teammates in Wrigley Field together for the next 20 years.

So in 1962, Zimmer had been let go, and the Cubs put 20-year-old Hubbs in the lineup, where he played 160 out of 162 games. In that Rookie of the Year season, Hubbs led all National League rookies in games, hits, doubles, triples, runs, and batting average. Even though his hitting cooled off in 1963, he was expected to bounce back. After all, one day he went five for five against Pittsburgh, and another day he got seven hits in a doubleheader. Cub broadcaster and future Hall of Famer Lou Boudreau expressed confidence that Hubbs’ bat would come around.

In the field in 1962, Hubbs was unbelievable. He set major league records with 78 consecutive games and 418 total chances without an error. His glove from 1962 is actually on display at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Major League Baseball named him Rookie of the Year for 1962 as did the Sporting News.

Not only was Hubbs a stellar fielder, but he was a sparkplug and a team leader. In the early 1970s, the Cincinnati Reds were good, but they didn’t become the World Champion Big Red Machine until they got Joe Morgan. Just as baseball fans think of Pete Rose and Johnny Bench and not necessarily Joe Morgan when they think of the Big Red Machine, fans may think of Billy Williams, Ron Santo, and Ernie Banks and not Ken Hubbs when they think of the 1960s Cubs. Hubbs performed a similar role as Morgan.

Ernie Banks said, “He was the zenith in inspiration and enthusiasm as well as desire and determination.”

“He had a real positive effect on the ballclub,” said Cub pitcher Lindy McDaniel.

Ron Santo ended up being the Cubs’ team captain in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but in the early 1960s Santo looked to Hubbs for leadership, even though Hubbs was only in his early 20s. For example, Hubbs urged Santo to quit smoking, and because Hubbs asked him, Santo did.

So in 1963, Hubbs’ batting average slipped a little, but his fielding didn’t, and the team finished over .500 for the first time in nearly two decades. Hubbs, along with future Hall of Famers Williams, Santo, Banks, and Brock were in the lineup every day, starting pitcher Dick Ellsworth won 22 games, and closer Lindy McDaniel saved 22 and won 13 in relief. In 1964, the team would be ready to contend for the first time for the first time since 1946.

Hubbs’ Cubs also would be ready to capture the hearts of Chicago fans. Few people remember that throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, Chicago was a White Sox town. The Sox contended every year, often finishing second in the American League, but the Cubs were never in the National League race.

Hubbs was a public relations professional’s dream. He was the quintessential suntanned, crewcut, all-American male, six feet two, popular with fans and teammates, religious, didn’t smoke, and didn’t drink, yet loved to have fun anyway. He always made time to do some charity work for children. “There isn’t a man in Chicago who wouldn’t have been proud to have him as a son,” said Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley.

It’s not outside the realm of possibility that when the Cubs started contending in 1964, Hubbs would have been to advertising what Mike Ditka was in the 1980s and Michael Jordan was in the 1990s. It’s likely that Hubbs would have been on TV commercials shaving, banking, and putting gas in his car, making the Cubs team, forgotten for nearly 20 years, the number one baseball team in Chicago fans’ consciousness.

Ability, looks, personality—Hubbs had it all. Unfortunately, he also had a fear of flying. With his strong personality, he took on this fear head on and decided to take pilot’s lessons in the winter of 1963-1964. In early February, Santo visited Hubbs at Hubbs’ home in Colton, California, and Hubbs gave Santo a ride in his Cessna 172. On Feb. 13, 1964, after playing a charity basketball game the night before at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, Hubbs piloted the Cessna 172 from Provo bound for Colton.

He never made it. In below zero, snowy weather, the plane crashed near Bird Island in Utah Lake, and Hubbs was dead.

About 1,300 people went to his memorial service. His funeral procession was two miles long. Almost every Cub traveled to Colton for the funeral. Cubs Santo, Banks, Glen Hobbie, and Don Elston were pallbearers. Colton shut down its city offices.

Hubbs died less than a month before spring training 1964, and his teammates never recovered. Santo was so upset that he consulted a priest. “I couldn’t understand it,” Santo said. “He was a great human being. This was a kid who didn’t even smoke or drink. Why him?”

So the 1964 Cubs, who were expected to contend, stumbled shellshocked into the season. By May 29, they were 16-22, and management panicked. Two weeks later, the Cubs made what was considered the worst trade in baseball history, sending Lou Brock to St. Louis for Ernie Broglio. The Hubbs-less and Brock-less clubs were done for 1964, and 1965 and 1966 as well.

But what if?

What if Hubbs had lived? Think about this lineup in 1964—and beyond. Brock leading off, Hubbs batting second, followed by Williams, Santo, and Banks. Every time Brock led off, there was the possibility of him getting a hit (he would end up being a career .293 hitter), stealing second, Hubbs moving him over to third with a hit or infield out, and Williams, Santo, or Banks driving in a run or two. The 1960s Cubs would have been as unstoppable on the basepaths as the Ozzie Smith-led Cardinals of the 1980s.

With Hubbs batting behind Brock and the team playing as confidently as in 1963 instead of in a depressed funk, there is no way management would have messed up the team chemistry and traded Brock.

And in the National League, 1964 saw one of those races in which the winning team—the St. Louis Cardinals— took the pennant with a mere 93 victories. (By comparison, the Dodgers had won the 1963 NL pennant with 99.) With Hubbs and Brock, the Cubs would have just as much of a chance to take the flag as any other NL team—and remember, Brock would have been with the Cubs instead of the Cardinals, pretty much knocking out the Redbirds as a contender.

Sports Illustrated in 1993 speculated that with Hubbs and Brock, the Cubs would have won the pennant in 1969, and every year from 1972 through 1975. With Brock and Hubbs in the lineup, the Cubs might also have won the NL pennant in 1967 and 1968 as well. In those years the Cubs finished third, and the Cardinals first. With Brock in Cubbie Blue instead of Cardinal Red, and with Hubbs hitting behind him, the two teams’ positions in the standings easily could have been reversed. My book The Forgotten 1970 Chicago Cubs: Go and Glow also points out that the Cubs finished only five games behind the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1970. Hubbs and Brock easily would have been worth five games, and the Cubs could have won that year, too.

Speaking of 1969, many fans and experts look back at the July 8 Cubs-Mets contest as the turning point, with the Mets beating the Cubs in the ninth inning when Cub centerfielder Don Young dropped two flyballs. Sports Illustrated speculated that Hubbs would have caught the first one, Brock would have caught the second one, and the Mets would have been dead.

Instead of the lovable losers, the 1964 to 1975 Cubs could have been one of baseball’s greatest dynasties—if only that Cessna had not crashed.

But the Cubs are not the only Chicago baseball team affected by a young infielder’s untimely death. The White Sox suffered the same pennant-less fate due to another tragic death.

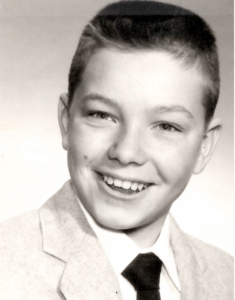

Just as Ken Hubbs was a multi-sport star in grade school and high school in the 1950s, so was a Chicago boy named Johnny Smolen in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Smolen was a basketball star for a North Side Chicago grade school, St. Sylvester’s, and a star Little Leaguer in Chicago baseball, in the late 1950s. In 1959, when Hubbs was just starting out in the minors, Smolen joined DePaul Academy, a high school affiliated with DePaul University.

Smolen quickly made the varsity basketball and baseball teams at DePaul Academy, and was a top swimmer, too. Another suntanned, crewcut, all-American male, a solid citizen just like Hubbs, Smolen also was popular with his teammates and classmates, who elected him vice president of his class. He was a National Honor Society member as well.

In baseball, Smolen played middle infield and was the quintessential five-tool guy. He could hit, hit with power, run, field, and throw. As a high schooler, he put up batting averages in the .400s and .500s.

All this talent attracted the baseball scouts, and the White Sox planned on signing him just as soon as he graduated from high school. That would have been in 1963. There was no draft then; teams could sign whomever they wanted, and the Sox wanted Smolen.

On the afternoon of Aug. 22, 1962, Smolen and seven of his buddies went swimming in Lake Michigan at Chicago’s Oak Street Beach. By 3 p.m. when his buddies couldn’t find him, they alerted the lifeguards. At 5 p.m., the lifeguards found Smolen’s lifeless body. Nobody knows how this expert swimmer had drowned.

DePaul Academy issued a statement that said, “John was a true example of Christian manhood and outstanding principles, his example showed the sprit of Christ, the beauty of soul and the training of DePaul Academy, of which he was justly proud. Let’s ask that his example will always encourage us to live and act in like manner.”

DePaul Academy held a basketball doubleheader in Smolen’s honor on Sept. 15, 1962, and dedicated its 1963 yearbook to him as well.

Again, what if?

What if Smolen had lived, and started his minor league career with the White Sox in 1963? If he was on the same schedule as Hubbs, he might have joined the team in 1966.

In 1967, the White Sox finished only three games behind the pennant-winning Boston Red Sox. And they did it with Ron Hansen at short hitting .233, and Wayne Causey at second hitting .226. Would a five-tool guy like Smolen have been able to take the place of one of those banjo hitters? No doubt. With Smolen in the lineup, would the Sox have been able to win at least three or four more games, and the pennant? Most likely.

Setting up a possible 1967 all-Chicago World Series, with Hubbs leading the Cubs, and Smolen leading the White Sox, in the Fall Classic.

Had the White Sox won the pennant in 1967, they never would have traded centerfielder Tommie Agee to the Mets in 1968, making it even more likely that the Mets would not have been able to beat out the Cubs in 1969.

In 1972, the Sox finished only five and a half games behind the eventual World Champions, the Oakland Athletics. Would a 27-year-old Smolen in his prime been worth six more victories? Again, most likely. And again, resulting in a possible all-Chicago World Series between Hubbs’ Cubs and Smolen’s White Sox.

Chicago has never seen an era in which the Cubs and the Sox were frequent pennant winners. If the Cubs and the Sox had been led by Hubbs and Smolen in the late 1960s and early 1970s, in major league baseball Chicago could have been titletown.

Unfortunately, we cannot know for sure what might have been, but with Hubbs and Smolen leading their respective teams we do know the history of Major League Baseball in Chicago would have been different—and better.

Editor's note: See sports journalist John Conenna's podcast for a lively discussion between Cubs expert William S. Bike and Conenna about Hubbs and Smolen.

The Forgotten 1970 Chicago Cubs: Go and Glow, published by The History Press of Charleston, SC, is available at https://tinyurl.com/1970ChicagoCubs.